Heritage

500 acres of fields, hills, woodland, lakes and formal gardens combine to create the stunning setting for Yorkshire Sculpture Park. These historic grounds were once part of the Bretton Estate, with a country manor at the centre. As well as housing hundreds of artworks, today the landscape is rich with the stories of Bretton’s former lives.

The Domesday Book listed this land as 'waste' in 1086. In the centuries since, it became an aristocratic home. And each of those who inherited and worked on the estate left their mark.

As beautiful as it may be, this landscape is not entirely natural. In fact, its previous owners had it carefully designed and managed to look 'natural'. Their architects, landscape designers and gardeners dug lakes, planted trees, built lodges. They also introduced extravagant, purely ornamental buildings – or follies. Among the wealthy landowners of 18th-century Britain, a folly was a fashionable status symbol, a display of excess.

Many of these fascinating features and romantic relics remain today. Seek them out in the grounds, dotted among the artworks, wildlife and trees.

People

A number of characters stand out in the history of the Bretton Estate.

In the 16th century Sir Thomas Wentworth had a beautiful bed designed for Henry VIII in case he ever visited Bretton. In 1720 Sir William Wentworth built the mansion that forms the centre of today's Bretton Hall. His son, Sir Thomas Wentworth, created a lot of the parks and gardens. Thomas was quite the eccentric, entertaining guests on and around his lakes with firework displays, mock naval battles and plenty of alcohol. On Thomas’s death in 1792, his daughter Diana Beaumont inherited the house and estate. This circumstance was unusual for the time, given that Diana’s father was unmarried and so she was considered illegitimate. Diana more than doubled the size of the mansion and had many glass houses and conservatories built. She was a forceful woman, and many people took a disliking to her. Her own son, Thomas Wentworth Beaumont, auctioned off everything that reminded him of his mother when he inherited the estate.

By the mid 20th century, the hall’s days as a home were over. Sir Alec Clegg, Chief Education Officer for the West Riding, oversaw the creation of the college at Bretton Hall in 1949. He helped establish the area as a pioneering and innovative place for education. Students at Bretton Hall College included opera singer Anne Collins; actors Shelley Conn, Mark Gatiss, Reece Shearsmith, Richard O’Brien, and Esther Hall; comedians Emma Fryer and Mark Thomas; playwright John Godber; and author Louisa Leaman.

In 1977 college lecturer Peter Murray came up with the idea of exhibiting sculpture in the landscape and opening it up to the public. And so, Yorkshire Sculpture Park was born. Clare Lilley took over from Peter as Director of YSP in 2022, until stepping down in 2025 when Kevin Rodd was appointed as Interim Director.

Buildings and Landscape

Lady Eglinton's Well

Creating an extravagant feature of a spring flowing down a rock face, this stone hut is one of the park’s oldest curiosities, dating back to 1685. The well backs onto the side of a former quarry, which provided stone for the hall and many of its features. A tablet above the doorway reveals that it was a tribute to Grace Countess of Eglinton. Grace was the widow of Sir Thomas Wentworth and continued to live at Bretton after his death in 1675, remarrying the Earl of Eglinton. A sculpted owl once guarded the top of the structure but has long since taken flight.

Obelisk

According to anecdote, the Obelisk on the northern edge of Bridge-Royd Wood marks the site of the original Bretton Hall. The first documented house here was built for Thomas Wentworth around 1508. He kept a magnificent, carved oak bed there especially for King Henry VIII, though it’s unlikely he ever slept in it. A sketch from the early 18th century shows that it was a rambling, timber-framed building. A fire damaged it in 1720 and work began later that year on a new house, completed in the 1730s. The old Bretton Hall was dismantled, and its replacement survives to this day.

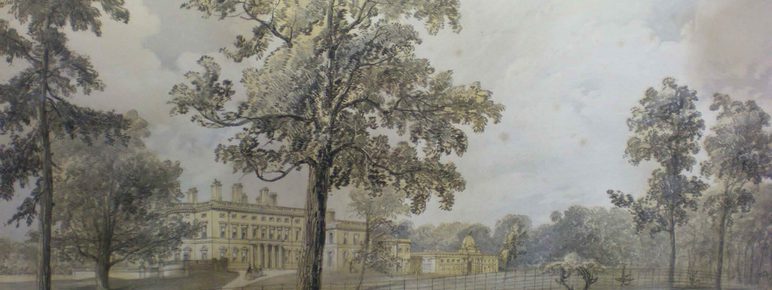

Bretton Hall

Bretton Hall was at the centre of life on this vast estate for over two centuries. Landowner Sir William Wentworth (1687–1763) had the Hall built in 1720. It evolved several times over the many years since. Under the direction of Diana Beaumont (1765–1831) the mansion more than doubled in size in the early 19th century. Little changed after that until the second world war, when the Hall was requisitioned. In 1948 Wentworth Henry Canning Beaumont sold it to the local council. A year later, it became a teacher training college for music, art and drama. The college closed in 2007 and the buildings were sold to Wakefield Council. The Hall is now being transformed into a hotel.

Chapel

When Sir William Wentworth inherited the Bretton estate, the closest church was six miles away in Silkstone. To make life a little easier for the family and its tenants, he had a chapel built on the estate itself in 1744. To pay for it, William used money left behind by his wealthy wife Diana Blackett, who had died two years earlier. Named St Bartholomew’s, the classical-style sandstone chapel was at the heart of Bretton life in the 18th and 19th centuries. Its small graveyard came to be the final resting place of many former inhabitants of Bretton Hall, starting with William. Renovated in 2013, the chapel is now a beautiful, contemplative environment for sculpture.

Lakes

Pleasure grounds were essential to English country houses in the 18th century. Winding paths for afternoon strolls. Intriguing plants and ornaments to discover. Places to pause and admire expansive views. The idea was to show off the environment in the best possible light. In the 1770s, Sir Thomas Wentworth (later Blackett) and his landscape designer began to re-envision the Bretton landscape. Though they may look natural, the two lakes were part of their plans. Thomas employed labourers to dig them by hand, starting with the Upper Lake. The Lower Lake followed, which Thomas wanted to be “big enough for Jonas and the whale”. Both were complete by 1782. The eccentric Thomas threw lavish parties on them aboard his 35-foot boat, the Aurora. Small islands dotted the lakes, where he put on firework displays and, at one point, housed an animal menagerie. Today, an island on Lower Lake is home to a colony of herons.

Boat House

The Boat House is a curious sight today, standing in a landlocked corner of woodland. It was built on the edge of the Upper Lake. But, over the centuries, the lake has shrunk, leaving the Boat House somewhat stranded. It once formed part of the estate's entertainment, back in its days as a pleasure ground for the wealthy. Sir Thomas Wentworth (later Blackett) had the lake and a series of islands created, and would sail out from here to impress his guests. Letters by Thomas in the 1770s and 80s talk of firework displays on one island, the Island of Venus, and a menagerie on another. All that remain of the original Boat House are its stone columns and mooring post.

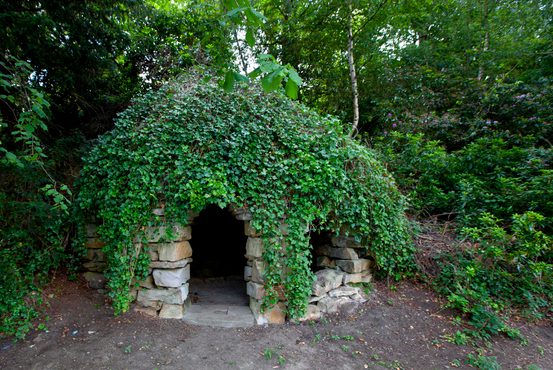

Shell Grotto

The Grand Tour was a rite of passage for young men of the privileged classes in the 18th century, taking in landmarks and treasures across Europe. It also had an influence on landscapes back home. Renaissance-inspired grottoes became common features in the gardens of the wealthy, including the Bretton Estate. The earliest grottoes in ancient Greece were pagan shrines to water nymphs. Here, the Shell Grotto was built on the south shore of the Upper Lake, and may even have housed a 'hermit' to entertain guests at one point. Anyone can now enter and admire the traces of shells that decorate the cave's walls, and the view from its window.

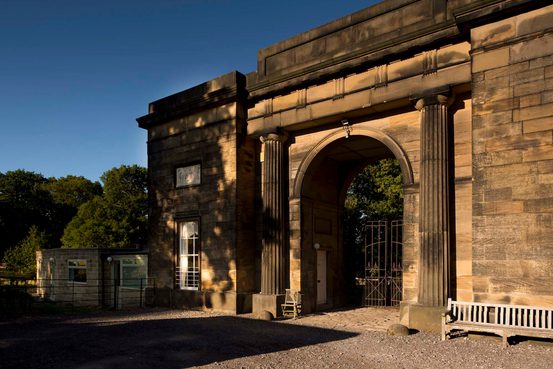

Archway Lodge

Few people left such a lasting mark on the landscape here as Diana Beaumont. Diana was at the helm of the estate from the late 1700s to 1831. In 1807 she enlisted William Atkinson, a top architect of her day, to build the Archway Lodge. It's a grand structure, with a pair of columns and a passageway wide enough for a horse and carriage. Standing at the top of a long track at the north-east end of the country park, it made for an impressive main entrance. Today, it’s a picturesque place for visiting artists to spend the night.

Camellia House

It's been said that Diana Beaumont was “loathed by everyone except her gardener and possibly her husband”. Landscape design was a passion of hers, so it's easy to see why a gardener might look on her favourably. For five years her head gardener was Robert Marnock, one of the 19th century's most renowned horticulturalists. Around 1817, Diana introduced the beautiful, glass-roofed Camellia House. Alongside it was a now-gone domed conservatory, thought to be the biggest of its kind in the world. Some of the plants in the Camellia House date back as far as the 1820s. They still flower every spring.

Greek Temple

The Greek Revival style of architecture was all the rage in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It was inspired, in part, by the Grand Tour, which saw upper-class young men visit Europe's ancient landmarks. It’s thought that Diana Beaumont had this imitation temple built as a summer house in the early 19th century. A spot for the family to sit and enjoy musical performances, perhaps. Uphill, on the edge of woodland, it affords a fine view over the Upper Lake and beyond. From up here today, visitors might reflect on the changes this landscape’s seen over the centuries – as well as all the things that remain much the same as in Diana’s day.